jQuery(document).ready(function(){

jQuery(“#slider-215502788.slides”).slick({

infinite: true,

centerPadding: “100px”,

responsive: [

{

breakpoint: 768,

settings: {

slidesToShow: 1,

slidesToScroll: 1,

centerMode: false,

centerPadding: “0px”,

}

},

],

});

});

function offsetFullBreak() {

var container = jQuery(“.article-con”);

var offset = jQuery(“.article-con”).offset();

jQuery(“.full-break”).css(“margin-left”,(-offset.left) );

jQuery(“.full-break”).css(“margin-right”,(-(jQuery(window).width() – container.width() – offset.left)) );

}

jQuery(document).ready(function(){

offsetFullBreak();

});

jQuery(window).resize(function(){

offsetFullBreak();

});

Undocumented parents confined south of inland checkpoints must choose between risking deportation or forgoing treatment for their child.

–

by Elena Mejia Lutz

@elenamejialutz

February 13, 2018

At 17, Lucia Ramos feared she would be killed or kidnapped at her home in the Mexican state of San Luis de Potosi. Terrified and poor, she crossed the Texas-Mexico border illegally in 1999. Years later, her fears came true as her brothers, who were involved in organized crime, were kidnapped from their home.

Lucia (not her real name) moved to Laredo, married and had a daughter three years later. Diana was born with scoliosis and no arms, possibly due to an undiagnosed genetic disorder. Without specialized care and surgery, doctors said, Diana’s backbone could eventually bend so much that it could cause her lungs, stomach and heart to shut down.

But Lucia found no doctors in Laredo who could give Diana the medical treatment she desperately needed. From 2002 to 2005, Lucia twice traveled with her daughter, a U.S. citizen, through an internal Border Patrol checkpoint for doctor’s appointments at Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi. Lucia feared deportation, but agents let her pass freely when she presented them with a binder of Diana’s medical records.

On their third trip to the hospital in 2006, Border Patrol agents at the same checkpoint detained Lucia for about six hours of questioning and deported her to Mexico. Fearing for Diana’s life instead of her own this time, she crossed the border illegally again in 2006 to care for her daughter. But with the threat of deportation looming between their home and the hospital, Diana’s condition went untreated for 11 years.

In July 2017, after hearing rumors that agents were letting undocumented parents travel with sick children, Lucia and her husband, who had a work permit, tried crossing the checkpoint again to take their daughter, now 15, to Corpus Christi doctors. But just as in 2006, Lucia was detained by Border Patrol agents and deported. Diana couldn’t travel without her mother, who she needed every step of the way, including for help going to the restroom. She returned to Laredo with her father, who also cared for Diana’s three brothers, Lucia said.

“If she would’ve gotten surgery years ago and received better treatment, her back wouldn’t be curved at almost 360 degrees,” Lucia said. “We were desperate because we couldn’t give her the help she needed. We could’ve given her a better life.”

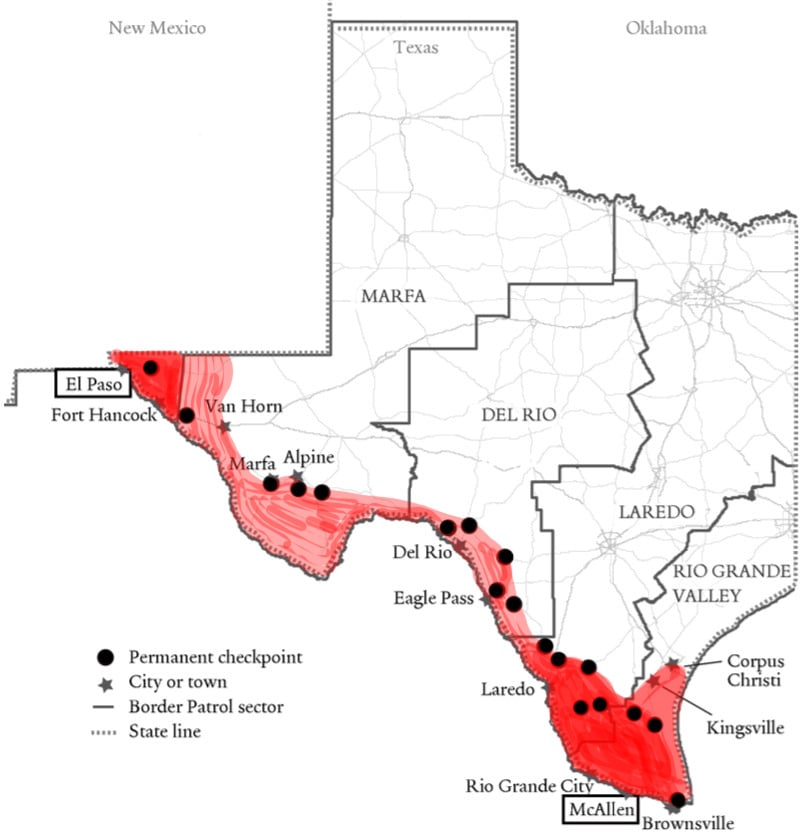

About 18 permanent Border Patrol checkpoints up to 100 miles from the border — stretching from El Paso to Brownsville — have trapped hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants and their family members in isolated border towns with few specialized health care facilities. In many cases, including Diana’s, seriously ill or disabled children with American citizenship cannot travel alone. That means some undocumented parents must make an excruciating choice between risking deportation or not getting treatment for their child. The fear of deportation has caused or exacerbated serious health problems for some patients, including citizen children. Many patients, like Diana, ultimately live with pain and the problem worsens until they might need more costly emergency care.

Immigration attorneys and advocates told the Observer the dilemma has existed for years, but has worsened under President Trump’s emboldened immigration force. The administration has clamped down on approving temporary authorization for undocumented immigrants to travel for humanitarian reasons, according to the attorneys and federal statistics. Before Trump, immigration agents were more likely to exercise discretion in some cases, deciding not to detain or deport parents with sick children or other extenuating circumstances. Now, all undocumented immigrants are on the table for deportation under a Trump administration directive that dismantled an Obama-era policy instructing agents to prioritize deportation of immigrants with a criminal background.

“The Border Patrol feels empowered to treat people differently now because they feel they have the law on their side when it comes to internal checkpoints,” said Norma Sepulveda, an immigration attorney in Harlingen. “Everyone is subject for removal.”

A few temporary legal options exist for undocumented parents who need to travel, but they are harder to get under Trump. Immigrants who have been deported or currently live outside the country can request humanitarian parole from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), which allows them to temporarily enter and travel within the U.S. for humanitarian purposes, such as caring for relatives with a serious medical condition. According to USCIS data, 96 percent of the 360,000 requests submitted in fiscal year 2016 were approved. But in 2017, only 85 percent of 416,000 requests were approved.

The Ramos family was lucky. In August, Lucia was granted a 30-day humanitarian parole, which allowed her to take Diana to the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children in Dallas. Diana is finally scheduled for life-saving surgery in mid-February.

But immigrants are unlikely to voluntarily leave the country to seek parole. Those living in the United States may request deferred action status or a stay of removal that allows families to travel without the risk of being deported. The application process can take several months — not an option for some people with serious medical conditions — and can be cost-prohibitive, said Jodi Goodwin, an immigration attorney in Harlingen. The permits are rarely granted for medical reasons and have become even rarer, she said.

“Since Trump, I have yet to get a stay of removal granted. Since Trump, I have yet to get a deferred action approved. Since Trump, I have yet to get anyone granted prosecutorial discretion,” Goodwin told the Observer.

Federal officials could not immediately provide the number of deferred action status requests or stays of removal, but the Observer has requested the data under the Freedom of Information Act.

Sepulveda said she’s seen an alarming increase in the number of undocumented people, including her clients, detained and deported at checkpoints while traveling to receive medical treatment for themselves or family members.

It is “pretty much a guarantee that they will be apprehended or put on the radar for removal proceedings” under Trump, Sepulveda said.

The issue was thrust into the national spotlight in October, when doctors in Laredo sent 10-year-old Rosa Maria Hernandez to a hospital in Corpus Christi for emergency gallbladder surgery. Border Patrol agents at the Freer checkpoint followed Hernandez, an undocumented immigrant born with cerebral palsy, and waited at the hospital as she received treatment. She was taken to a shelter for unaccompanied children in San Antonio and later released after the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a lawsuit. Hernandez’s deportation proceedings are ongoing.

Carla Provost, Trump’s interim Border Patrol chief, issued a memo last month outlining the agency’s long-standing policy on medical care and checkpoints. “Immediate emergency operations should always receive expedited transit through or around checkpoints,” the policy states, but family members traveling with patients “are not exempt from an immigration inspection.”

The policy instructs agents to use discretion during “follow-up inspections or immigration interviews … at the hospital.” Carlos Diaz, a spokesperson for U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), said the guidelines were in place under past presidents.

“It is a matter of how these rules are enforced, not a matter of what the law is,” Sepulveda said. A section in the CBP memo notes that “each circumstance will need to be addressed on a case-by-case basis with guidance provided by leadership.”

Marsha Griffin, an American Academy of Pediatrics spokesperson, said that the Rio Grande Valley — like most of rural Texas — suffers from a physician shortage. “But we happen to be south of the checkpoints,” she said.

Griffin, a Brownsville physician who has practiced for more than a decade in the Valley, said she has seen cases in which premature babies born to undocumented parents near the border must travel alone by helicopter or ambulance. Under Trump, the climate for undocumented immigrants who need health care is “probably the worst” in the last decade, she said.

“If parents go [with their children], they can be permanently separated from their child,” Griffin said. “They’re not violent criminals. And that’s where we are.”

The post At Border Patrol Checkpoints, an Impossible Choice Between Health Care and Deportation appeared first on The Texas Observer.